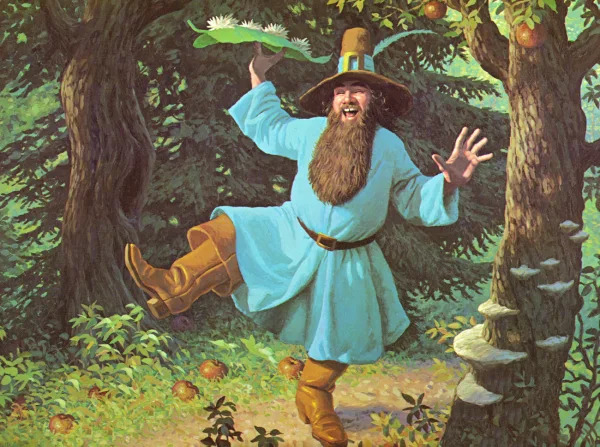

“I am Gandalf, and Gandalf means me.”

Names reveal character in Middle-earth.

Sauron is evil; Tom Bombadil is benevolent. Hobbiton is familiar; Lothlórien, mysterious. As soon as you read their names, you know that to be true.

These people and places are creations of J.R.R. Tolkien – the author of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion.

Tolkien’s choice of names tells us something about the way he thought about language.

Take note if you want your writing to be as rich as the story of Frodo and the One Ring.

As linguists go, Tolkien was a tweed-clad rebel

In The Two Towers, a tree giant explains, “Real names tell you the story of the things they belong to…”

The line neatly sums up Tolkien’s theory of language. He thought the sound of words directly connects to their meaning – a fringe view in the 1950s.

Back then, the field of linguistics was dominated by structuralists: scholars who insisted a pig was called pig because of historical accident, rather than because there was something inherently hog-like about the word.

(If there was, why would the Dutch for girl be pige?)

But Tolkien was entitled to his opinion. He knew 35 different tongues, both ancient and modern – everything from Old Norse to Lithuanian. And, when he invented languages for Middle-earth, he made sure the sound of his words made sense.

The Elvish word for snow is olosse. The word for metal is tinco. They could hardly be the other way around.

Scientists have accepted Tolkien’s thinking

Those Elvish words reminded me of an experiment from 2001. People were shown the two shapes above and asked to assign names. They had to label one bouba and the other kiki.

Which one suggests bouba to you?

Quickly now. Come up with your answer.

If you went with the right, you’re in agreement with 95% of the study’s participants. And the reason for your choice might have to do with the way your mouth moves.

There are connections between the sensory and motor areas of the brain. So you could be linking the visual shape of the object – either round or spiky – to the shape that our lips make when we say that corresponding word – either open and rounded, or narrow and wide.

Poets agreed with Tolkien all along

The earliest poetry was made to be read aloud. So it’s no surprise that poets are alive to the music in everyday words.

Mary Oliver, in her ever useful The Poetry Handbook, points out the difference between rock and stone:

“Stone has a mute near the beginning of the word that is then softened by the vowel. Rock ends with the mute k. That k suddenly stops the breath. There is the seed of silence at the edge of the sound. Brief though it is, it is definite, and it cannot be denied, and it feels very different from the -one ending of stone. In my mind’s eye I see the weather-softened roundness of stone, the juts and angled edges of rock.”

The inventor of Elvish would be pleased.

I’m not sure the two versions of Elvish distinguish between rock and stone. But there is gond for boulder and sarn for pebble – sounds which suit their subjects.

Tolkien relished the taste of language – so should you

For Tolkien, learning a language was like ‘trying a new wine’. It was delicious… intoxicating… an experience to be savoured.

With novels and poems, he invited readers to step through his cellar door and sample his findings (including cellar door, which he argued was the most beautiful phrase in the English language).

So when you next have to name something, take your time. Your choice will tell a story.