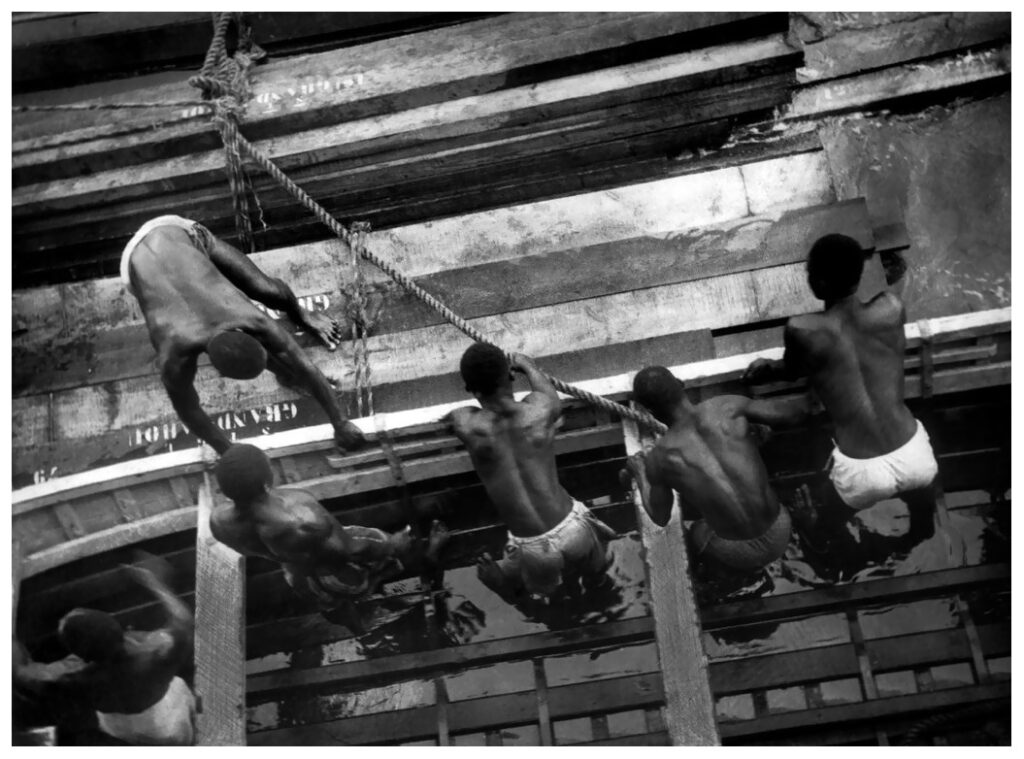

He watches, half-hidden

The street around the construction site is flooded. Water mirrors everything.

Each man has a double, a reflection that captures their movement and their dress – each man, except the hunter behind the fence.

The hunter stands in dirt, peering through rough-cut planks. And he shoots. The result is a photo of a divine second: the moment a passer-by leaps over the wet, sending their shadow flying.

The photo was Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare. It was taken in 1932. And it startles.

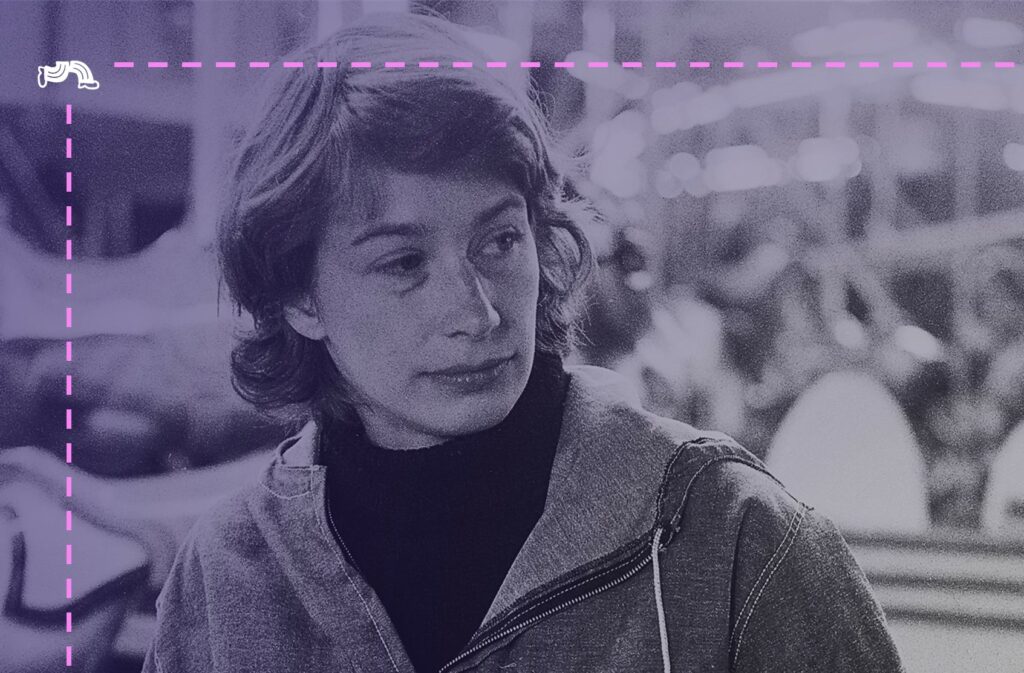

Essayists (like myself) use the iconic snap to introduce Cartier-Bresson

That would be the name of our prowler behind the view-finder: French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Now, with the photo comfortably situated before you, any essayist worth their salt would observe that Cartier-Bresson has captured a “decisive moment”.

Despite the rubble and the peeling posters in Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, there is a “structure of sensuous and intellectual pleasure and recognition of an order that is in front of you.”

Fancy words. For, at this juncture, the essayist won’t be able to resist quoting Cartier-Bresson himself.

Look at the image. Do you get a giddy feeling? Vertigo, perhaps? Is it as though you’re seeing something you’re not supposed to see?

Cartier-Bresson has suspended the scene, so that we can see the secret structure of a split second, down a chaotic backstreet in Paris.

“The difference between a good picture and a mediocre picture is a millimetre.”

Most essayists would call your attention to that stuff, anyway

I’m more interested in the fence. Why was Henri skulking?

In the small Leica camera – painted black so it was less conspicuous in his hands.

In the dark border around the famous photo: proof it was printed at full frame. No cropping.

That’s why Henri Cartier-Bresson should be introduced as a hunter

Without this connection, how do you explain the ritual Cartier-Bresson observed into his nineties? Whenever he got a new camera, he’d test it by shooting ducks in the park.

What? You want more proof? Fine…

The English-language edition of his book was titled The Decisive Moment. But it was called Images à la sauvette in France.

How does that translate? Images on the sly. Hastily taken images.

And they were. Early in the book, he outs himself as an apex predator:

“I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to ‘trap’ life — to preserve life in the act of living.”

Besides, hunting is central to his life story

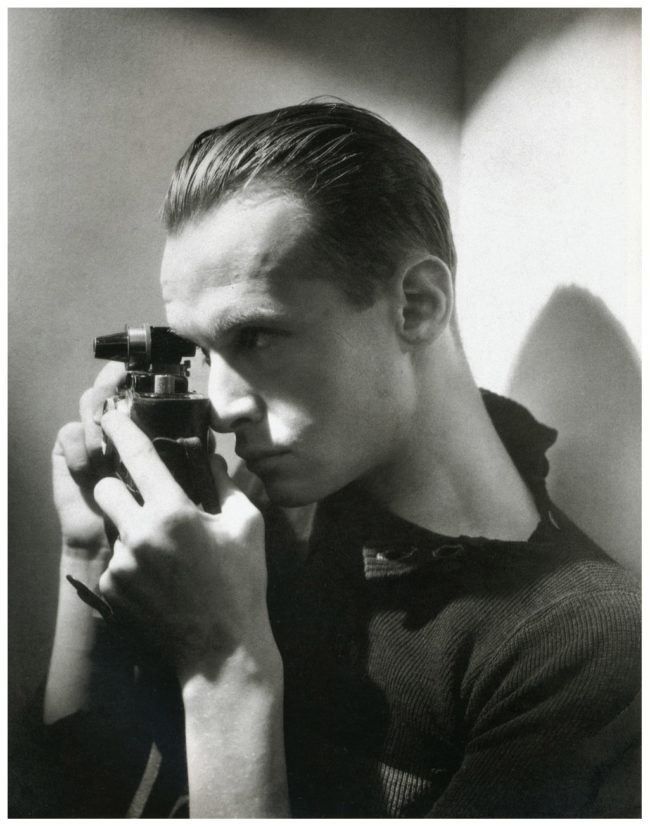

In 1929, he was in the army, but he wasn’t fighting for the Republic. He was under house arrest for hunting without a license.

The intervention of one Harry Crosby saved him. And the American serviceman took young Cartier-Bresson home. And why not? The pair had much in common. They shared a passion for photography, and for Crosby’s wife.

Romance led to heartbreak for the Frenchman. And, inspired by Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Cartier-Bresson sought distraction on the Ivory Coast.

He hunted game and took photos. The pursuits were much the same.

“To take a photograph is to align the head, the eye and the heart. It’s a way of life”

A gun doesn’t make a hunter

I could comb through antique stores for the same model of camera Cartier-Bresson used… I could pick up a 50mm lens and eschew colour film… It wouldn’t do any good. I’d lack Cartier-Bresson’s essential equipment: his eye, his heart, his head.

But I can take his philosophy and apply it to my art. I can carry a small notebook. I can listen in at the bar. I can scribble down choice phrases.

I can strip copywriting back to its essentials, away from focus groups and Large Language Models. I can take the words spoken in the street and give them new order. I can hunt.