I did it

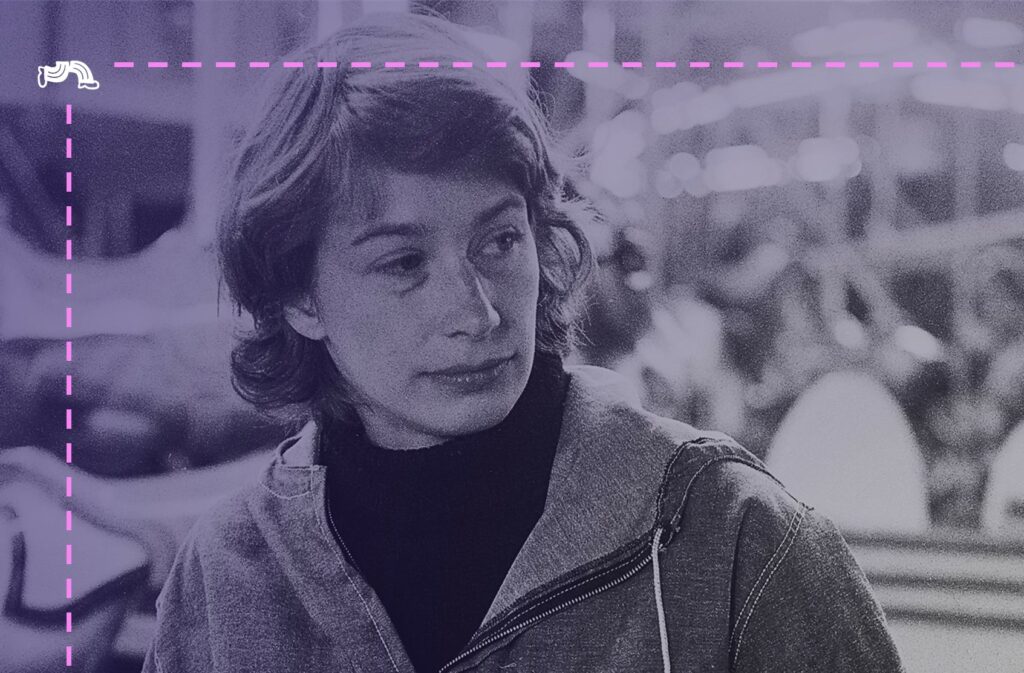

I’m now the kind of writer who manages other writers, which is… weird.

Great! It’s great to be an associate creative director. But… weird.

What’s it going to be like? I can only guess. So I asked an old boss of mine, someone who upgraded from Adobe Suite to the c-suite many moons ago, “What’s the truth?”

Was it – as rumours would have me believe – going to be like herding tigers?

“No,” came the response. “Herding cats is about right.”

“Treat creatives as you would a pedigree kitty. Offer up food and affection.”

Sage advice. But Miles Davis can do better.

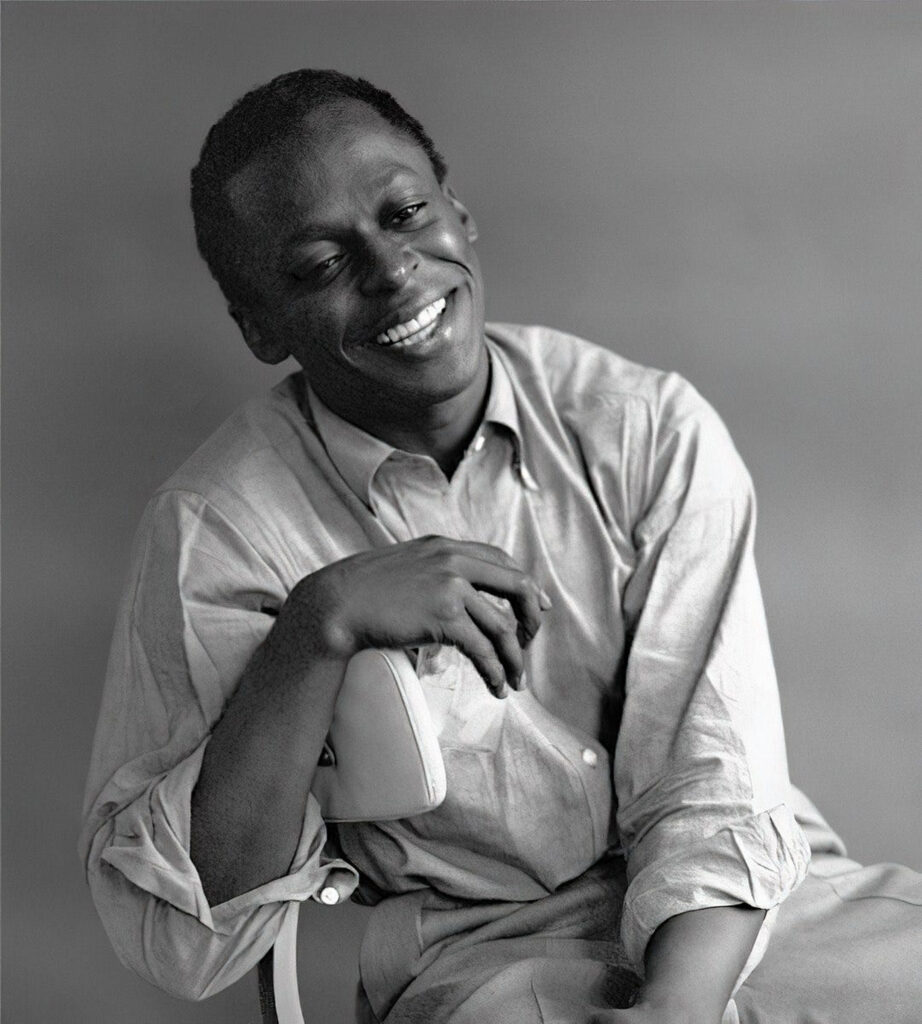

The jazz trumpeter really knew how to assemble a team.

Lesson one: ACD is a conservative job title

I like to think Miles Davis prized his unconventional job titles more than his nine Grammys.

“Magician.”

“Sorcerer.”

“Zen teacher.”

The nicknames were given to Davis by members of his band – a shifting cast of jazz musicians who learnt from Davis’s oblique instruction.

Miles Davis opened minds and valves by saying things like:

“Play the space.”

Or:

“Play like you don’t know how to play guitar.”

There was method in the mayhem. According to Davis’s official biographer, Quincy Trope, the goal was to whip up:

“… a maelstrom of music. Everything swirling around him, going in different directions at once. And he was at the centre, directing everything like a mad scientist.”

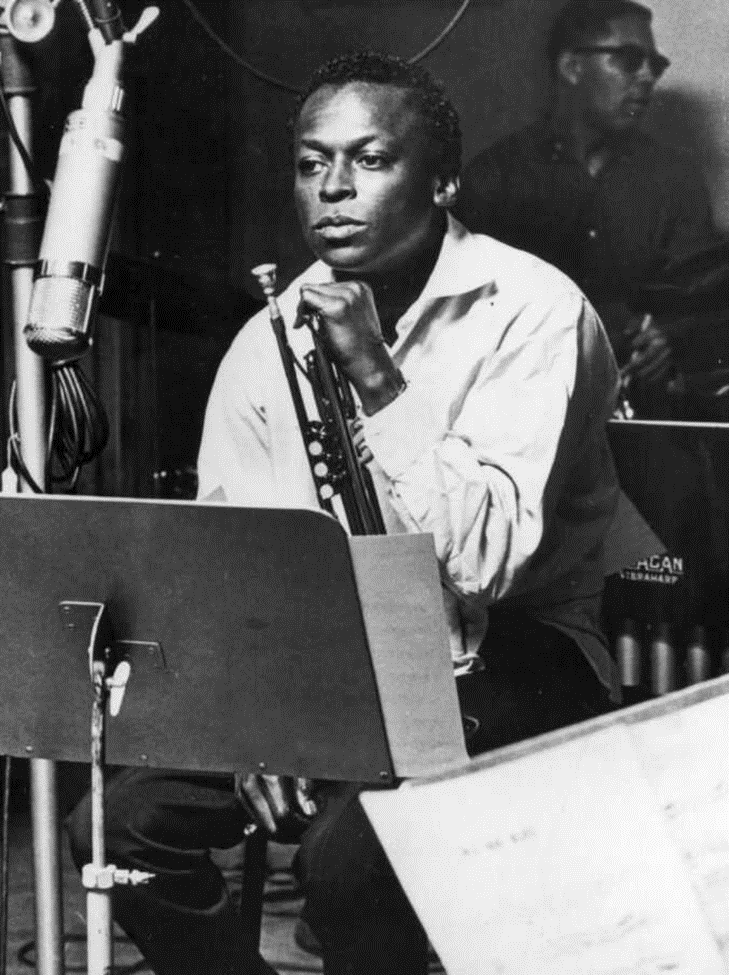

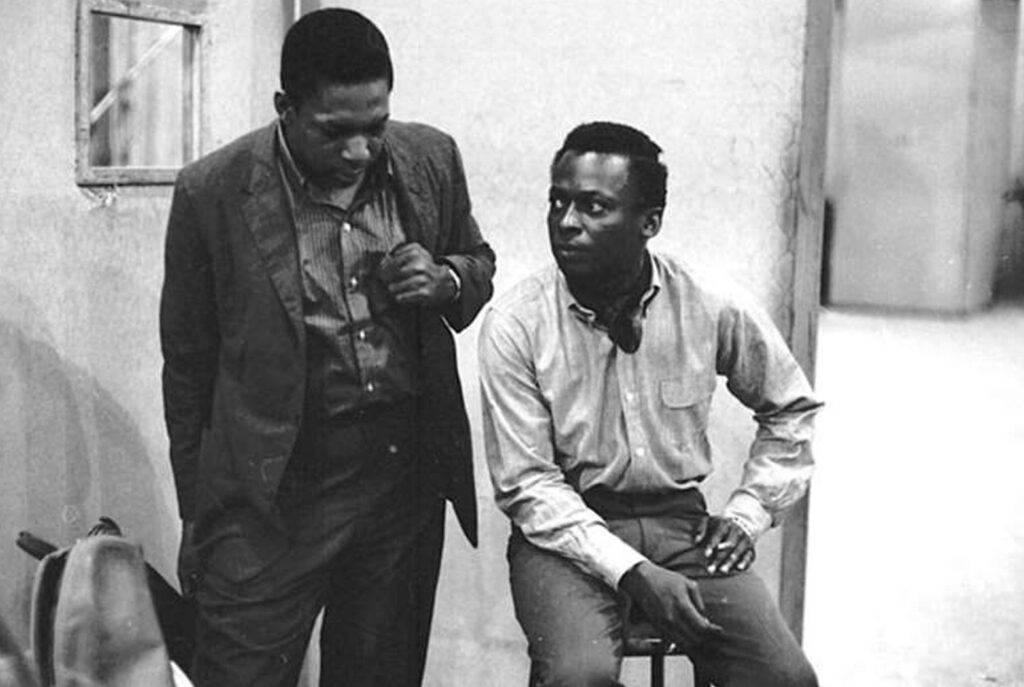

Miles Davis mixed players like volatile chemicals. And the blend of Davis and John Coltrane was particularly potent.

It led to Kind of Blue.

Three months. Two explosions. One record-breaking album.

Things got worse before they got better. And certainly before they got epoch-making good.

We can hear the main beats of Davis and Coltrane’s relationship by listening in on three episodes.

September 1955 – an audition.

October 1956 – an explosion.

March 1959 – a second explosion, creative this time.

In September 1955, Miles Davis was making calls. He couldn’t tour without a saxophonist.

Cue Coltrane, who blew into New York to audition. And he presented Davis with a performance that sounded like a practice session.

Coltrane repeated phrases. He shuffled notes like a card shark trying to come up with a winning hand. Was he fumbling? No.

Miles listened to the fanfares… the flourishes… and he understood.

“People have creative periods, periods where they *snap, snap, snap*, like that, you know? I recognise it in other people.”

Coltrane became part of a quintet. Playing off Davis, he made the group funky but cerebral, full-on but laid-back.

Davis reminisced:

“After we started playing together for a while, I knew that this guy was a bad motherfucker who was just the voice I needed on tenor to set off my voice.”

October 1956: Coltrane was wrestling with demons named heroine and hooch. But he refused to wrestle Davis.

He sat in spaced-out silence as the band leader berated him in Café Bohemia, New York.

Coltrane had embarrassed his boss in a string of clubs with rumpled clothes… a nodding head… nothing behind the eyes.

Now, he took Davis’s lashing – verbal and physical. They’d stay loosely tied for another six months, by which time Davis was tired of all the “junkie shit”.

Everything looked better by March 1969. What’s more, everything sounded sublime.

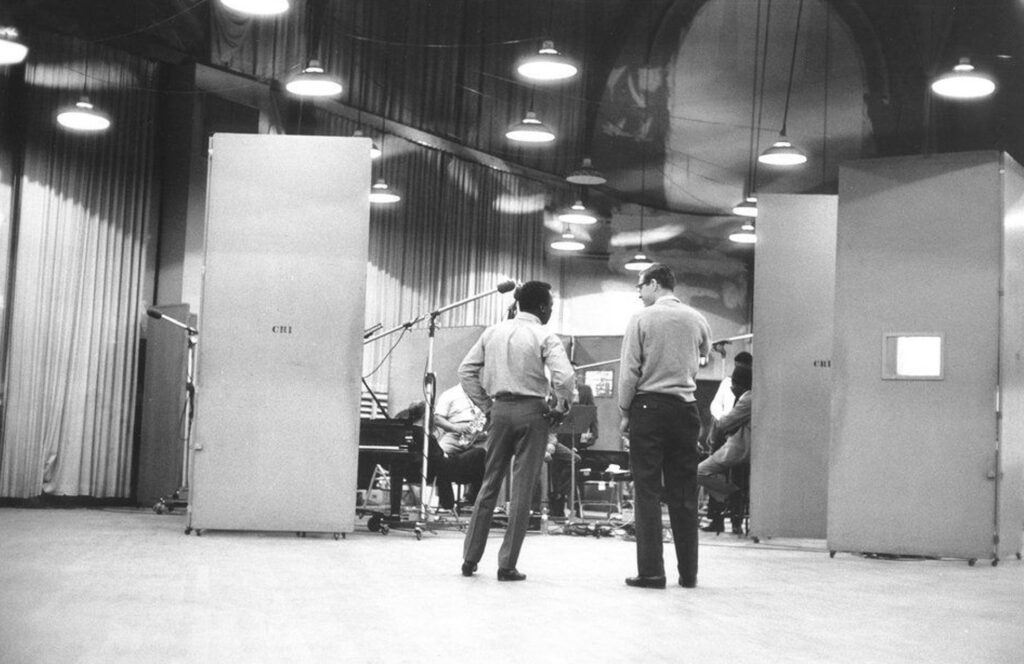

Tapes rolled, recording Kind of Blue for posterity. And Miles and Contrane were together again. They played without rehearsing.

In the memory of Wayne Shorter – another member of the Kind of Blue sextet – they:

“… just looked at the music, went over it a little bit and then recorded.”

That matches Davis’s account:

“I told the musicians that they could do anything they wanted, play anything they heard, so that’s what they did.”

If Davis ruled over a maelstrom of music, Kind of Blue was the eye of the storm, the point where everything cohered and just made sense.

It stands as:

“… an example of pushing boundaries and taking experimentation right up to the edge of failure in the pursuit of something new.”

And that judgement comes from Harvard Business School professor Robert Austin. So you just know we’re going to glean some work lessons from the record.

Class is in session

We spoke about titles before.

“Teacher” was one that stuck with tar-like stickiness to the heels of jazz-man Miles Davis.

Even as Coltrane led bands of his own, he referred to Davis as “The Teacher”. Capitalised with reverence, of course.

And we can take a seat in Miles Davis’s classroom, if we reflect on what we’ve heard.

Okay, so this is actually lesson one: don’t be afraid of talent.

Davis saw Coltrane’s rough, ambitious playing in the audition room and wanted it close. The trumpeter gave Coltrane room to range – even going so far as to leave the stage himself.

Lesson two: throw down provocative challenges.

Remember the zen riddles like “Play the space”? Well, there was more from where that came from. Miles again:

“We used to talk a lot about music at rehearsals and on the way to gigs I’d say, ‘Trane, here are some chords but don’t play them like they are all the time, you know? Start in the middle sometimes and don’t forget you can play them up in thirds. So that means you got 18, 19 different things to play in two bars.’ He would sit there, eyes wide open, soaking up everything.”

You don’t widen eyes, slacken jaws and stretch minds through tedious instruction.

Lesson three: compete with the greats

Davis kept a loose grip on process. He worked towards Kind of Blue like a method actor. He immersed himself in genius, then found it in himself.

Bartok, Stravinsky and Schoenberg imparted wisdom through recordings of classical music.

The composers influenced Davis’s arrangements. For “Blue and Green”, he put together ten bars, instead of the typical eight or twelve.

That’s something a sextet would usually rehearse. But Davis wouldn’t hear of it.

The band that recorded Kind of Blue wasn’t to be micro-managed. Davis trusted them to change music.

So they did.

Lesson four: know when to let go.

John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Bill Evans all graduated from “Miles University”. And I say “graduated” deliberately. At some point, they all left.

After 1969, Coltrane was a soloist, bandleader and composer. What’s more, he was sober. Another of Davis’s gifts to music.

So, know when to let go of processes. And know when to let go of people, too.

Aidan Clifford shares business lessons from creative icons. He writes for Pinstripe Poets – artists who love their day jobs.