“I still have an innocent curiosity about how things go… All I’m trying to do is get everybody off the highway and, if anybody follows my lead, they’ll soon be lost too.”

We’re all test subjects

It sounds like a conspiracy theory. But it’s true.

Our behaviour is analysed; our spending is tracked; our choices are studied by MBA graduates in air-conditioned rooms.

And robots watch closely, too.

Algorithms learn what we like from thousands of signals: likes, saves, shares, comments, follows, dwell time. Your phone monitors everything short of salivation and pupil dilation to predict where your dollars will flow.

It’s all a tad Big Brother. But the results are far from dystopian. The more businesses put us under the microscope, the more they learn; the more they learn, the more they give us what we want.

Experimentation is the engine for progress, ease, longevity, and bargain shopping.

eBay is an easy case study

The company wouldn’t exist without its website. It’s where people go to browse, bid, make payments – and that’s when eBay takes their cut.

So no website, no eBay. Yet rather than handling the website carefully, eBay’s managers try to break it in small ways, every day.

They’ve experimented with thousands of aspects of the site. But they don’t hit all their users with the change straightaway. That would be vandalism.

Instead, they put an altered version of the website in front of a random set of visitors. If the visitors respond well, the change becomes permanent.

That’s how eBay became beloved by bargain hunters: one experiment at a time.

The tests led to the site we hover around today — the site with large high-quality images, countdown clocks, security features and tabs for choosing between shipping and payment options.

How can you go from white mouse to white coat?

Knowledge is power – and experimenters accrue both. So how can you put yourself on the other side of the two-way mirror?

Or to be more literal about it: how can you operate like eBay — going from being the subject of studies to being the kind of businessperson who runs experiments of their own?

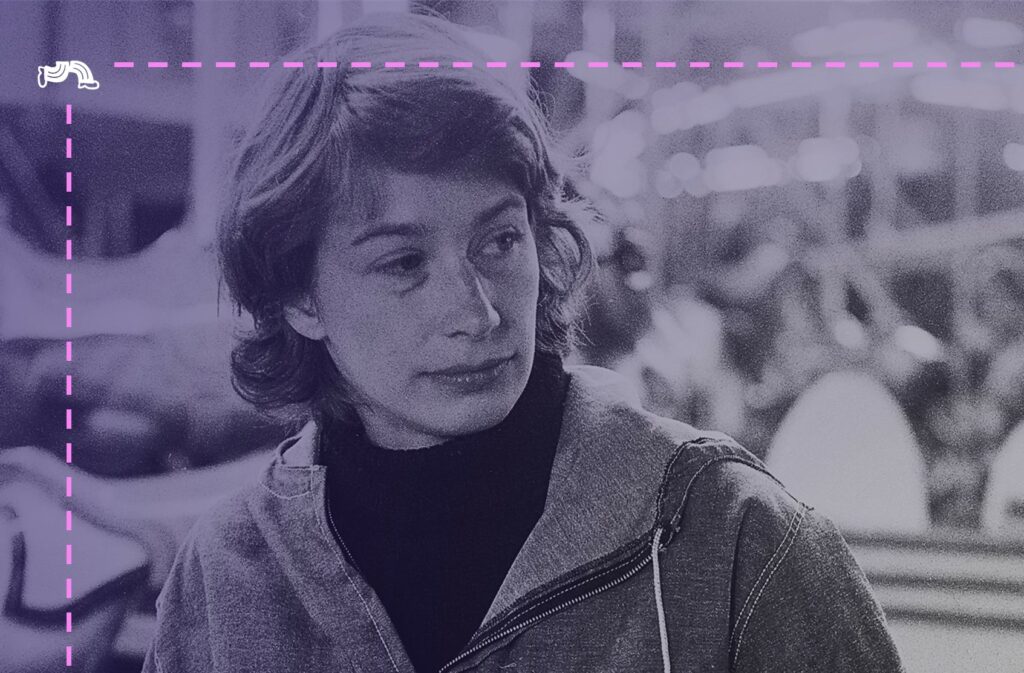

Learn from Robert Rauschenberg

That would be a good place to start.

He was a painting, sculpting, litter-picking, roller-skating pop artist who lived a life of enquiry. His ethos?

“Screwing things up is a virtue. Being right can stop all the momentum of a very interesting idea.”

By screwing up, by screwing around, he investigated. He researched small technical matters, like “Can you print photos with vegetable dye?” And asked goofy, profound questions, like “Can a box filled with dirt be art?”

Plenty of teachers, curators and po-faced New York painters tried to shrug him off. To which Rauschenberg had a retort: he was too busy to care.

“You have to have time to feel sorry for yourself if you’re going to be a good Abstract Expressionist. And I think I always considered that a waste.”

The young pup was insistent. He wouldn’t stop. He just kept seeing, feeling and thinking – to the extent that one critic called Rauschenberg “a perceptual machine”.

When you leaf through a catalogue of Rauschenberg’s work, it’s like tuning into a restless stream of consciousness. Now, the following quote is made up. It’s what I hear in my head when I flick through his drawings, paintings, installations and shows:

Okay – forget the box of dirt. How about a pebble tied to a piece wood? Is that art?

Or the imprint of a car tire?

A bed pinned to the wall?

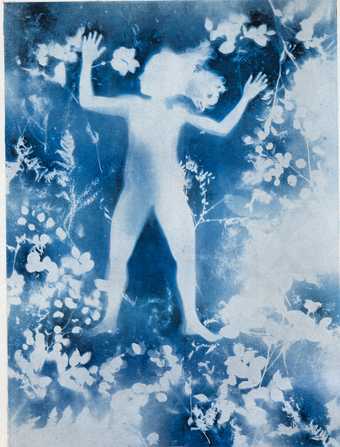

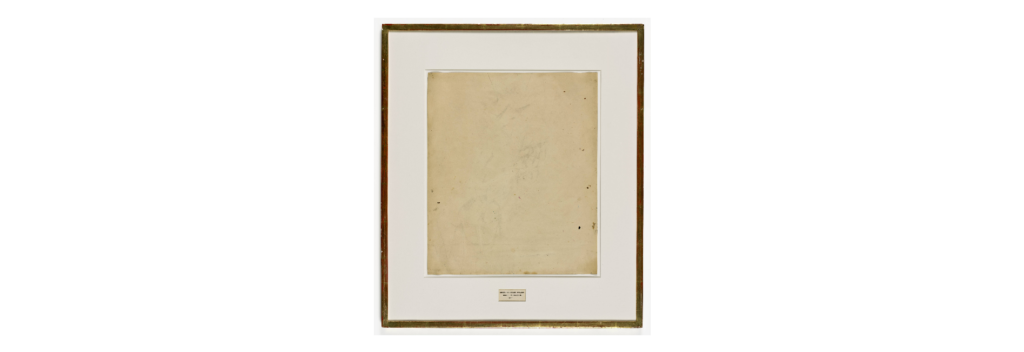

Now, you’d say a drawing is art, but what about an erased drawing?

What if the original drawing was by De Kooning?

What if De Kooning drew something that was intentionally hard to erase, so I’d have to spend two months rubbing until I was back to the blank page? Then could I call it art?

Huh? Huh?!

Erased de Kooning Drawing by Robert Rauschenberg (1953)

Pages pass. And you reach the end of the catalogue. How will you feel then?

Will you feel inspired — charged up by exposure to unfiltered creativity?

Or despondent at the thought, “I’ll never approach that level of genius”?

Both reactions are valid. But take heart. There are lessons to pluck from the life of the artist. Lessons that will grant you an experimental mindset, making you better at your job.

They might even nudge you closer to genius.

Lesson one: try opposites

Rauschenberg began painting after leaving the US Navy at the end of the Second World War.

In the 50s, Jackson Pollock dominated the art scene. You can get a sense of the fandom from the catalogue of his first exhibition. It described Pollock’s talent as:

“volcanic. It has fire. It is unpredictable. It is undisciplined. It spills out of itself in a mineral prodigality, not yet crystallized.”

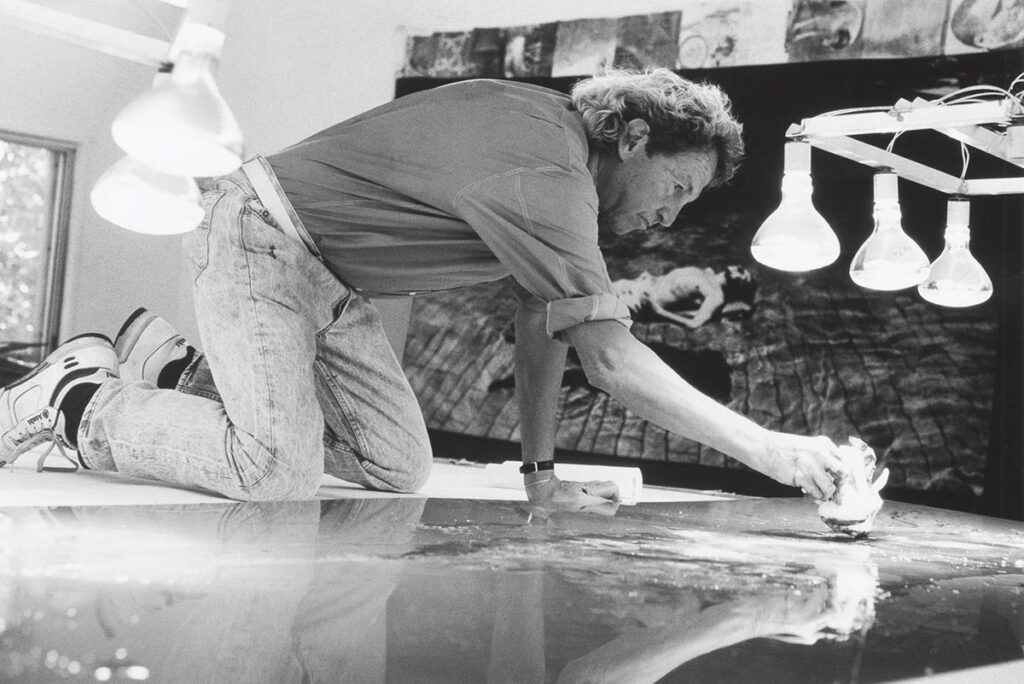

Pollock had many imitators. But Rauschenberg stood apart. He bucked the trend for messy, gestural artworks by producing flat white paintings – smooth, unembellished surfaces that almost looked like blank canvases. Almost.

It was an absurd experiment. But the experiment worked.

Composer John Cage described the white paintings as “airports for the lights, shadows and particles”. Rauschenberg himself said that they were affected by ambient conditions, “so you could almost tell how many people are in the room.”

Then, having made the opposite of a Jackson Pollock painting, Rauschenberg inverted his own work. He followed the white series by applying glossy black paint to scrunched-up newspaper.

There’s something in that approach. As creative leader Rory Sutherland is fond of saying:

“The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.”

So if you’re stuck for new ideas to test, try inverting your usual practices, or studying the methods of competing firms in your sector, before promptly doing the opposite.

Lesson two: combine ideas

Speaking of breaking the mould in your sector… You should be learning from other industries.

Mike Cessario is sage on this topic. He founded the water company Liquid Death after wondering:

“Why aren’t there more healthy products that still have funny, cool, irreverent branding?”

The brand doesn’t use the tried, tired imagery of nature, health and mountain springs. It packages itself — both literally and metaphorically — like an energy drink.

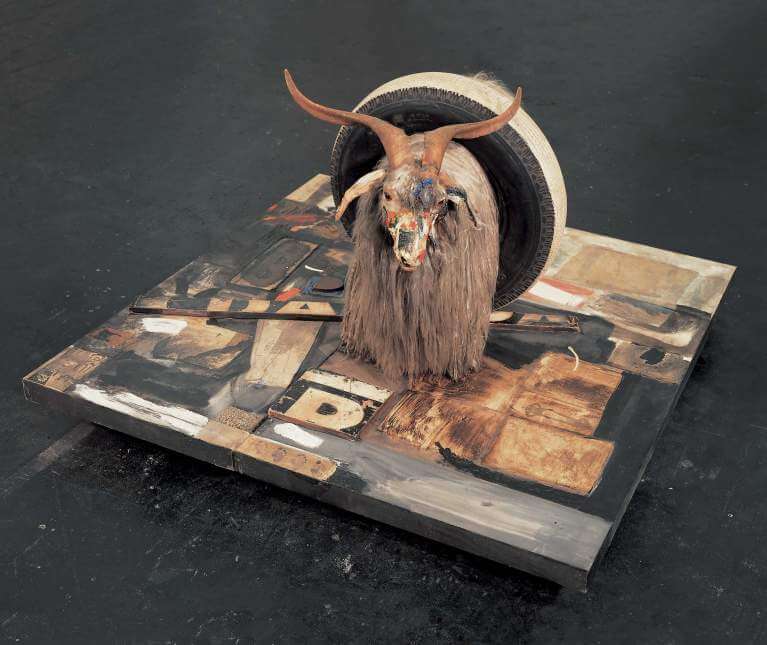

Rauschenberg would have looked at the canned water as a “Combine”: the combination of existing materials and symbols to make something exhilaratingly new.

The pop artist used the same label for works which blurred the line between painting and sculpture. His piece called Monogram used oil, paper, fabric, metal, wood, a shoe heel, a tennis ball, a rubber tyre and an Angora goat from a junk store.

By presenting objects in a new context (in this case the context of the gallery) and in relationship with each other, Rauschenberg made them exciting.

In art – as in business – one plus one can equal three. So try to peer beyond your company and immediate competitors. Look outwards. (Hang on. That could be a lesson in of itself… Something about summoning the zeitgeist.)

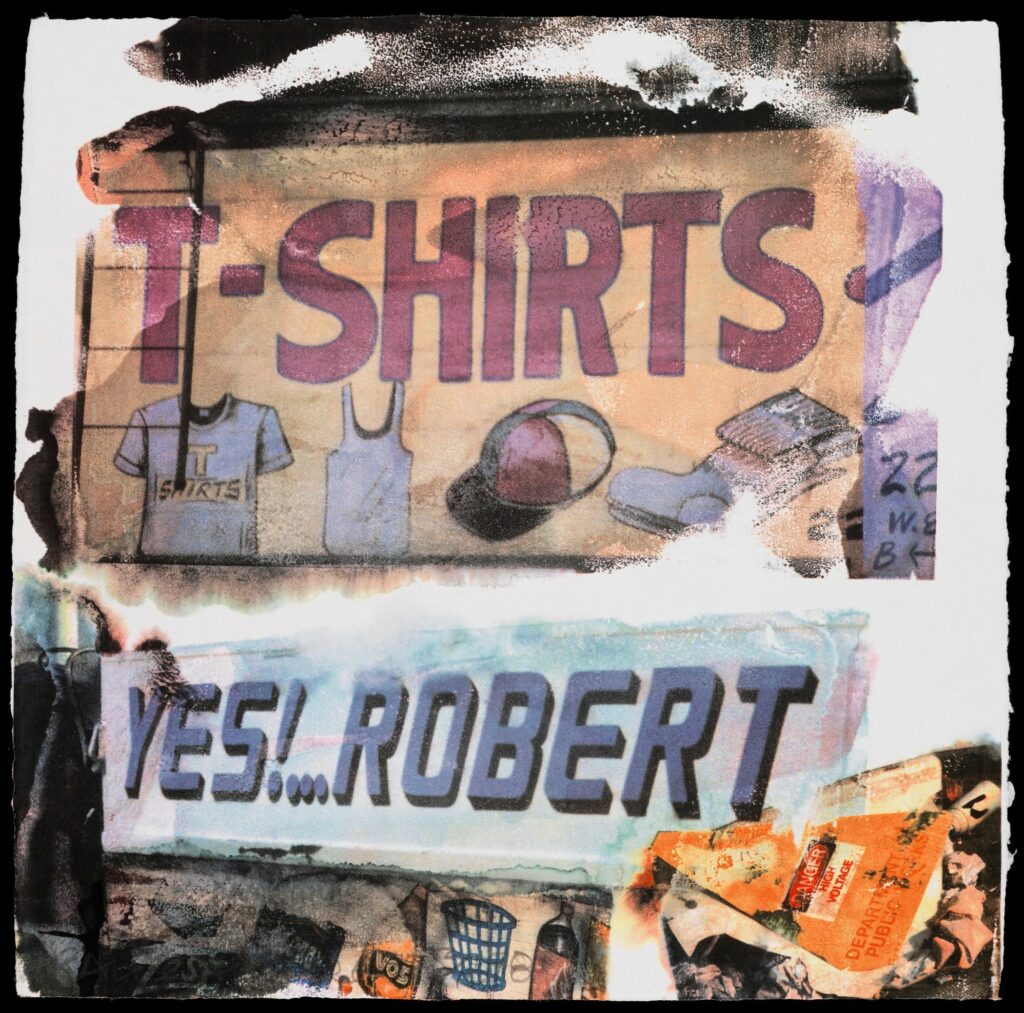

“I want my paintings to look like what’s going on outside my window rather than what’s inside my studio.”

Lesson three: tune in

Rauschenberg saw the potential for beauty in almost everything. And he had great sympathy for purveyors of taste, the snobs who haunted auction houses:

“I really feel sorry for people who think things like soap dishes or mirrors or Coke bottles are ugly, because they’re surrounded by things like that all day long, and it must make them miserable.”

Rauschenberg, meanwhile, was happily surrounded. America in the Cold War era was awash with goods and media.

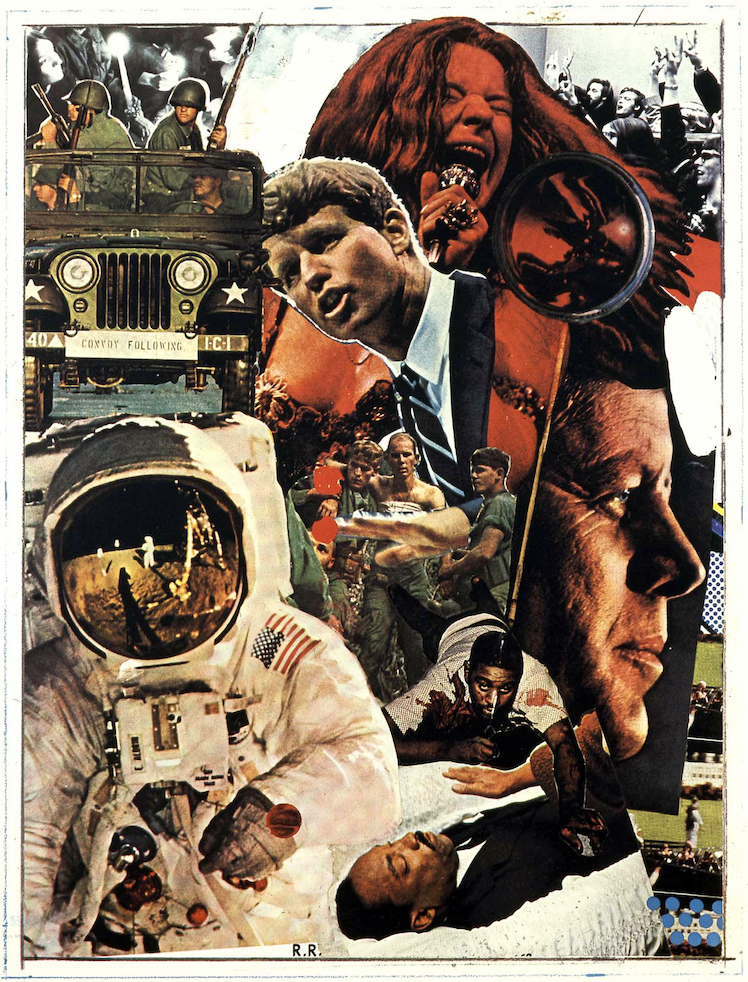

Newspapers rustled with astronauts and presidents. Magazines heaved with actors and rockstars. Television flickered with athletes and activists. Rauschenberg wanted a piece of them all:

“I was bombarded with television sets and magazines, by the excess of the world. I thought an honest work should incorporate all of those elements.”

Andy Warhol taught Rauschenberg how to scavenge images like some multimedia magpie: through screen-printing, photographs could be transferred on top of his paintings, where they could be juxtaposed and complemented by other images.

Honesty, openness, and an insatiable appetite for mainstream culture. Those are three positive traits that helped Rauschenberg as an artist.

Being wide-eyed in wonder would help you as an experimenter, too. Any job that involves reading other people’s thoughts becomes easier when you’re on their wavelength.

Lesson four: start movements

Large experiments at eBay take months of graft and involve specialists of all kinds. The same could be said of Rauschenberg’s collaborations.

Rauschenberg worked with diverse creatives and technologists. They sparked the artist’s best ideas.

Ideas like…

Oracle — scrap metal wired to make sound;

Soundings — a lightbox layered with ghostly chairs;

Mud Muse — a gurgling tank of bentonite clay;

And, of course, 9 Evenings: Theater & Engineering — an event that brought together visual artists, dancers, choreographers, scientists, and engineers.

The people who worked on 9 Evenings didn’t want the party to end. So they formed a non-profit organisation called E.A.T. or Experiments in Art and Technology.

Rauschenberg was content to share the glory. He thought art emerged from a moment, rather than a man:

“It is completely irrelevant that I am making them – Today is their creator.”

Art historians regard E.A.T. with fondness. In the opinion of Dr Kathy Battista, the non-profit’s biggest idea caught on:

“Today it is common practice for artists to work with musicians, architects, engineers, scientists and other professionals. E.A.T. was the model for such collaboration and its egalitarian spirit was an inspiration.”

How could you use the E.A.T. model in your organisation? Who would sign on? It’s worth thinking about. You can only do so much alone.

Dream. Test. Do.

Okay, so you’re unlikely to have a billion web visitors like eBay… or the profile of a controversial modern artist like Rauschenberg. But you can still experiment.

You might start by testing different subject lines for emails. Or by starting meetings at five past, rather than right on the hour. The important thing is to begin.

Experimentation can make leaving your comfort zone feel like an adventure, rather than a death sentence. And if you repeat that adventure, day by day, you’ll come to agree with Robert Rauschenberg:

“I’m not interested in doing what I know or what I think I can do.”

How boring to stick to what you know, when there’s no end to the alternatives. There are impossible stunts to try. And sure, you’ll fail. You’ll fail plenty. But does it really count as a failed experiment if you learn something new?

Aidan Clifford shares business lessons from creative icons. He writes for Pinstripe Poets – artists who love their day jobs.